Today was a perfect day for toe-digging. Toe-digging is the time honored tradition of harvesting mussel shells by wading in shallow water and feeling for the shells with your feet. In the winter, the lake depth drops dramatically and mussels can be found in ankle deep water. There are only a handful of days a year that the wind is almost still on Ky Lake, and today was one of those days. It was a nice break from diving, wading around and picking up shells.

The water was so calm and clear, that most of the shells I harvested today were by sight. I could look and see shells for several yards before I got to them. One of the good things about the prices being so low right now (actually about the only good thing) is that there is almost no competition out there. When the prices are good, there are divers and toe-diggers on every shallow bar on the lake. Today I didn't see one other diver on the lake.

Who knows what tomorrow will bring?

It's important to stay focused when you are doing something dangerous. If it's driving a two ton car at 60 down the highway, or crawling along the bottom of the river with surfaced supplied air, you've got to keep your mind on the task.

When you've been doing something for many years, it's easy to start thinking you are bullet proof. That is a dangerous state of mind, you become careless and that can get you killed. Yesterday the wind was up and the lake was white capping. I knew the only way for me to dive was to drive my boat a couple of miles against the wind and let it drag me through the shell beds. I started out from Danville and went just passed the creek channel in front of Bass Bay. There is a strip of ebony shells along the river bank there that I have been working. Before I jumped in, I looked back down the path I would be working. The wind was going to drag me across the creek channel which was about 25 feet deep, no big deal, it was only about 20 yards wide. But there were channel marking buoys on each side of the creek, I thought to myself, "I'll probably get my hose wrapped around one of those buoy cables". No big deal, just a little inconvenience.

When I got my suit on and compressor started I hooked my weight belt around my waist, tested my regulator, adjusted my mask and jumped in. The wind quickly caught the boat and it was all I could do to slow it down enough to grab shells as they went by. The waves were pulling me up and down but I've dove in a lot worse. Before long, I reached the edge of the creek channel and started down, there were a few shells on the bank and along the bottom. As I started up the far side I was wrenched to a halt. I thought "yep, hit a buoy". Since I was 25 feet deep the waves were really jerking me up and down now as I felt around behind me for the cable. That was the weird part, the cable had snapped itself unto my weight-belt hook. We have our air hoses attached to our weight-belts by safety snaphooks. That way we can easily unhook them if we have trouble. But by a freak accident, this buoy cable had gotten lodged in the hook along with the ring on my belt. Since the waves were slamming me up and down, I had to wait for the lull between waves to work on it or risk losing fingers. I was at the point of ditching my belt and surfacing (which I really didn't want to do) when I finally got the hook off my belt. I had just a couple of heartbeats to unsnap it from the cable and back on my belt before the wind and waves jerked it out of my hands. It was a little hairy, but over in a couple of minutes and I was back up the bank and grabbing shells.

This little experience reminded me that what I do for a living can be dangerous. We are in a hostile environment dependent on surface supplied air. I have lost good friends who were excellent divers, but it only takes one bad accident to end a life. I have been diving for 37 years, all my adult life and half my childhood, and never had a cable snap onto my weight-belt like that. Just like driving a car, you need to stay alert and focused at all times. Don't be lulled into thinking you're too good for something bad to happen. As Ra's al Ghul told Batman, "Mind your surroundings!"

In the early days of the mussel industry, the market was primarily for mother-of-pearl buttons. Until the advent of plastics in the 1930s, mother-of-pearl was the sturdiest, most beautiful and cost efficient material available for the clothing industry. As plastic gained a firm hold in the 1940s, the mussel harvest industry almost ground to a halt. It was shortly after World War II that one of America's enemies saved the freshwater shell business from extinction.

Early 1950s: a man named John Latendresse became interested in freshwater pearls and made his way south. When he found musselers (at the time basically amatuer treasure hunters and free divers) in Tennessee he offered to buy any pearls that they might find. Latendresse's passion soon led him to Japan and a new international industry was born. Japan had the first cultured pearl farms in the world, but had trouble finding high quality mother-of-pearl to implant into their oysters. To meet this need, Johnny Latendresse founded Tennessee Shell Company in Camden, Tennessee in 1954. Mussel shells from the Tennessee River soon proved to contain the highest quality mother-of-pearl in the world. This started a fresh boom in the mussel harvest game and introduced a new generation to the proffession. The Mussel Diver was born as a direct result of Latendresse's dreams and hardwork. Over the next four decades, this had an enormous impact on the economy of West Tennessee, particularly Benton Co.

Latendresse went on to found the American Pearl Company in 1961 to import Japanese cultured pearls into the U.S. This ignited another idea and passion and Johnny began a quest to gather the closely gaurded secrets of the cultured pearl. On one of his fact finding missions to Japan, Johnny was told by the CEO of a major pearl company, "We don't feel you belong in the Japanese pearl business. Mikimoto is a natural hero, we began it and we don't feel you belong in it." Latendresse snapped back with, "Henry Ford is our national hero, but look what Toyota and Honda have done with his ideas." Latendresse gathered what information he could and with over a decade of trail and era, the American cultured pearl industry was born.

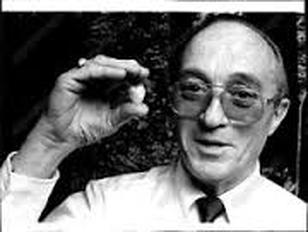

John Latendresse and his wife Chessy admiring pearls.

My father met Latendresse (dad always called him Johnny) in 1979. After four years of mussel diving in four states, my father Rayburn 'Big Frizz' Frizzell, had gained a reputation as one of, if not the best diver on the water. When he came to Benton County, Johnny contacted him and asked to buy his shells. (There is a funny story about their first meeting, but I will go into that on another blog.) A friendship and business relationship was formed that spanned two decades and was mutually beneficial. My dad soon became a buyer for Tennessee Shell and in 1984 started the first dive shop geared towards the mussel diver, Big Sandy Dive Shop. Latendresse recognized the business potential of my dad, and Rayburn soon became the head shell buyer for the company. He not only had his shell camp in Big Sandy, TN, he also had buying stations in KY, OK, AL, IL, LA, and TX. My entire family was employed at the various shell camps. My brother, Bruce Frizzell, began buying at the Big Sandy camp when he was 15. Within a couple of years he took over buying at a shell camp catering to the brailers in Kentucky. When Johnny sold Tennessee Shell in the early 90s (for a reported 10 million) my dad was head of exporting and was getting a commission of .025% on every shell shipped, which at the time amounted to 3 million pounds a year. Rayburn Frizzell sold Big Sandy Dive Shop to Tennessee Shell and retired soon after Johnny Latendresse sold the company. John Latendresse passed away in 2000. His family still owns American Pearl Company in Nashville, TN.

John Latendresse is now known as the 'Father of American Cultured Pearls', and for good reason.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed